Sam Grieve was born in Cape Town and lived in Paris and London prior to settling down in Connecticut. She has a BA from Brown University and an MA from King’s College London. She has worked as a writer, librarian, bookseller and antiquarian book dealer, and consequently has never found a home with enough bookshelves. She is published in the current issue of A cappella Zoo and has work forthcoming in Grey Sparrow. She is married, has two sons and a dog, and an extended family who live far away over the sea.

~~~

Our father was dead. A month before, he had suffered a heart attack on his way to work, had collapsed on the red polished stairs that led up to the mining office. A gardener, hands soiled from planting nasturtiums, had carried him inside and placed him in the shade of the front hall, out of the burning sun, an utterly pointless exercise as he was dead already, the doctor explained. When my mother heard this, she turned her face to the wall as though this act of kindness was too much too bear; but Agnes and I emptied our piggy banks and changed our money into a single pound coin that we presented to the man in the company gardens.

His name was Solomon, and the whites of his eyes were yellow, like the yolk of an egg.

~~~

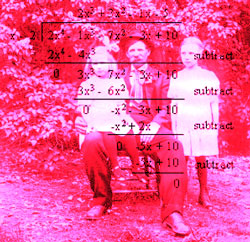

Our father was an accountant, the son of an accountant, bred for the mental gymnastics of numbers and their infinite acrobatics. He was tall, just over six foot, but when standing, he subsided into himself as though his core were made of something yielding. Even his voice was soft. If he were in a room, it was unlikely you would notice him, unless, perhaps he was sitting in your chair. That was his way, to efface himself, and yet when it came to mathematics, he was supremely confident. His greatest trick was mental arithmetic; while other fathers told jokes and stories, built kites and paper boats, or picked up their little girls and swung them in the air so that their feet flew above their heads, ours would sit us on his knee and answer our most devious mathematical conundrums, stating the solutions in his calm voice as though the integers were just floating in the air, ten inches from his nose.

“I see mathematics in colors,” he once told us, and I believed him, for when he was working with numbers, his face took on such an expression of wonder; it truly could be assumed that all the colors of the rainbow were exploding before his eyes.

~~~

For my father, numbers and their egregious logic was the language most familiar to him, but to his despair, neither my sister nor I could make any sense of it. As young children we walked home from school with our nanny, our brown cardboard school-cases banging against our thighs, heads hanging. Other homework was always conquered first: our spelling lists, our grammar, our chapter books, while we waited for our father to come home and make sense of the numeric problems we had been set. That numbers could divide in half, and come together, could be shattered into pieces, could be multiplied against each other, could never end, seemed impossible. Night after night our father persevered with us, and in silence Agnes and I sat there, our pencils wet in our mouths, his words flitting like moths above our heads. Sometimes I would almost grasp something; the waters of the pool would settle as the agitating wind drew back, and I would glimpse with perfect clarity the stones and silt that lay below. But then the wind would rise, the waters would rustle, and all understanding would be gone. In exasperation our father would push back his chair, rise from the table, and head out into the night with his long loose stride.

He gave up on us as we grew older, came to accept our failings, but because we could not communicate with him in his common tongue, our house fell into two halves — his: masculine, numeric, clear-minded, hardworking, organizational, and ours: daydreaming, errant, lazy. Our mother had not gone to school; she had been educated by a governess, and badly at that, and so there was no expectation that Agnes nor I should show any inclination toward schoolwork. We were left to our own devices, and we reveled in it, our freedom, dressing up, putting on plays in the gazebo, digging for diamonds in the veld, climbing trees, and making mud pies in the curve of the river. Sometimes our mother joined in our fancies, sitting with us on the lawn to eat the wild strawberries gathered for a doll’s picnic or showing us how she could skip, the rope a gray blur around her body, but more frequently she suffered from migraines and lay in her room, a towel over her eyes.

~~~