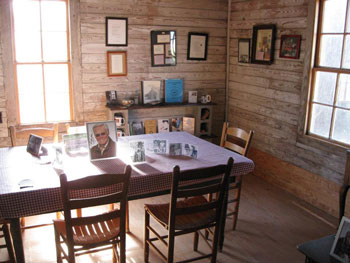

photo of the Plankhouse by Wade Allen

I.

The awesome mist of some unknown flower

Sprindges my voice into my father’s words —

This plantation’s not what we used to work,

When Pap George, his father, David, held our

Future in slavery, though we knew that its hour

Had come: I think of the women —

July — Obedience — skimming

Rocks on Middle Creek; still it hurts

Me now to think of all the things

Human beings have done that brings

Heartbreak to families, with laws,

I mean, that must be overthrown and all —

II.

I know, yes; let me tell you, can you hear?

What Nin and I have done to hold the past

Awhile in our hands, arms, and eyes at last:

We revised the plankhouse you had rolled back

In the hedge, the mules straining muscles with no slack

Of power behind family;

You hired men to build a lovely

Home, ranch-type, after Mama flashed

Her eyes at you; you knew they said,

“You spend more money, Paul, on Red,

And the rest of those dogs, than you

Do on us; we really need a house, too.”

III.

All that I think about — and the graveyards —

Their flurry is real as my back-muscles

And my longing to tell about scuffles

We boys would start to see who was stronger;

We’d wrestle — lift sacks of fertilizer longer

Than we should; turn the Mason jar

To our lips, let the brandy wear

Our natural prime — muscles —

We knew we were born to work hard,

And play hard, too — to twelve o’clock,

Saturdays, then run to baseball.

I could play all evening, then court my doll.

IV.

Maytle Samantha Johnson, your “Dumpling,”

You called her; she didn’t mind — her calling?

Help raise us children; work through our squalling

She quieted with a lullaby, falling

Into a soothing trance-like spell, never failing

To stop our crying: her picture

The mantel holds, yours, too, cigar

Between your teeth, like you’re scalding

A hog in the vat, around men,

Swearing, drinking liquor for strength,

The liveliness of God’s world — told —

You yearn to hunt the fox in autumn’s gold.

V.

Sometimes I’m out of tune, bad: I ought to

Believe in plumbing — planting pretty shrubs;

But I wanted the old well and its curb

In our basement, case we needed water.

We never did: fancy bathroom? — I’ll use the woods,

I said: that room? Best in the house,

Though doing business with a mouse,

Behind the barn, among the scrubs

Of sassafras — why, that’s heaven,

To hunker down — get earth — level.

I’m not sure I got there, the old

Plantation way died, but never did fold —

VI.

I know — go on away — like hymns of night —

Just know that your accounts are on that wire

You strung them on: your desk? That wire and nail.

And Nin and I sit on the porch, all right.

She thinks Fifties on Paul’s Hill must have been a sight —

The pace: slow for going fishing,

And running the dogs, too, wishing

We could see the fox, red or gray,

Didn’t matter — we heard music,

Which I hear now, an acoustic

Frailing you played on your banjo.

Maybe this is a prayer: I hope so.

VII.

For smoker’s everywhere I do not cease

To name Kents, Salems, Viceroys I have smoked;

The frilly hints of mist or mythic toasts

That make studs out of boys; models: Clarice

Becomes Virginia Slim; Stud struts Marlboro streets,

With muscles big as billboard-poles,

And wide as sunset ever gold.

I smoked Kools, left my lungs alone.

Nicotine fingers turned yellow,

Oh, my Maytle, tasting that sour,

Sideways odor, my mouth, sallow,

As if a chicken roosted there — pray — tell.