Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6

The day the new online catalogs arrived in the library marked the beginning of the end of Mrs. Lilah Lamb’s 25-year-library career. Or perhaps it was the day Mr. Chesterton, the new director, stepped into the library a year and some months earlier, in January 1984, a year for technological bodings.

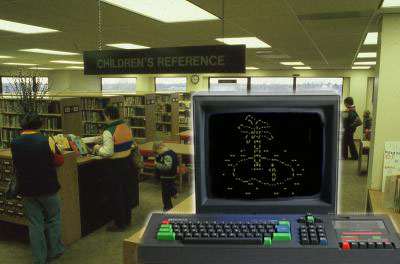

Mr. Chesterton was leading the Irving Public Library into the electronic age with the library board’s blessing. He even tried to make the transition to automation as painless as possible. To let patrons and staff get used to electronic browsing gradually, he decreed that the computer terminals should be placed on the cabinets that housed the cards. That way, people — he sometimes said Luddites — could test drive the new catalogs but still consult the cards, should they be intimidated by the computers. The card catalog ceased to be reliable, though, because new acquisitions no longer were added to it. The stage had been set for the time when the cards would disappear entirely.

Lilah, Head of the children’s library, was herself a Luddite and proud of it. She regarded the machines as invaders, an occupying force ostensibly there to help, but in reality waiting to perform a coup and usurp power from the rightful ruler, the venerable card catalog. She waged a futile guerilla campaign to save the cards. When patrons began to experiment with the electronic catalogs, she sympathized with their frustrations.

Ms. Mary Hoskins, mild-mannered reference librarian in the adult services division, scolded Lilah and counseled her against careless remarks.

“You mustn’t be rash, dear! Give it time.”

The two had been housemates and lovers for nearly twenty years. Mary knew well Lilah’s strong will and tendency to obsess over matters in the Children’s Library. Two competent assistant librarians had quit, because they couldn’t tolerate her inflexibility and need to control every detail of management and organization.

A “steel magnolia” from a well-to-do southern family, Lilah had long been a Midwesterner but was aware of the charm of her honeyed accent, using it selectively when it worked to her advantage. The former library director, also a genteel, southern woman, had felt a kinship with Lilah and had given her free rein to administer the children’s library.

Lilah’s arbitrariness and exactitude did not diminish Mary’s affection. In fact, she had a certain fascination with this part of her partner’s personality, even as she sympathized with the victims of it.

Professionally, Mary was competent, objective, open-minded, and interested in new technology. She preferred working with adults or older students, and, if the truth be known, would have been better suited to a career in an academic library. She’d long ago given up that aspiration when Lilah persuaded her to apply for the position at Irving Public Library. She was a poet who’d had a few of her poems published in literary journals.

Lilah had worked with children her entire career. She loved children but also had a mission. She regarded herself as one of the last bastions in protecting innocent young minds, and she practiced censorship liberally under the guise of responsible collection development. Because Irving was a conservative community, Lilah enjoyed some loyalty and support among mothers. She resisted modern writers of realistic, young adult literature like Judy Blume, transferring their works to the adult fiction section if possible.

The fact that Lilah herself lived an alternative lifestyle that many conservative members of the community might find objectionable was tucked away in a compartment of her mind that she rarely opened. She and Mary had a tacit agreement that they should present themselves as merely companions who shared a house for the purposes of companionship and economy. For Mary, this charade was a pragmatic solution. Perhaps if they’d lived and worked in a broad-minded academic community, she would have been open about the relationship, but she cringed at the thought of being ridiculed in Irving.

Lilah had once been married briefly and had a daughter, Darla, who was now 27 years old and lived in California. Lilah’s husband was an alcoholic abuser, who had died in a drunken driving accident two years after the divorce. She’d retained the Mrs. title, not just for the sake of camouflage, but because it was important to her self image. In fits of pique, she developed a revisionist version of her marriage, speaking of her former husband in, if not glowing, at least adequate terms and assuming a slightly condescending air toward Mary.

For her part, Mary endured these episodes stoically, as she did Darla’s vague disapproval of her. Usually, Lilah spent one week of the three weeks’ vacation due her visiting Darla. It worked out well. It helped to give them the image of having separate lives and saved Mary from suffering through an awkward visit with Darla and a seaside vacation.