Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6

Mary did not share her partner’s love of beaches. Too much sun gave her a rash, and the smell of coconut oil made her nauseous, and she was self-conscious about her tall, thin ungainly figure in a bathing suit. She also thought it the height of folly for people to bake themselves in the sun.

Her tastes in vacations ran to browsing the Smithsonian or strolling through Williamsburg, cruising Skyline Drive in its early fall brilliance, or, best of all, touring the Louvre and European castles. She and Lilah had done all those things. But, still, Lilah had this affinity for the ocean.

On a cool, rainy day in mid-April, Mary sat in a program at the annual state library association conference, staring gloomily out the window, thinking there was no way to deny Lilah’s plans for a vacation on the beach of North Carolina. She had tried persuading her to spend a week or two in a mountain cabin in North Carolina instead, but Lilah wouldn’t hear of it. Darla had “special projects and business trips” which, translated, meant that she had a new man in her life, and Lilah felt she should not impose. Instead, she insisted the two of them would have a nice seaside vacation.

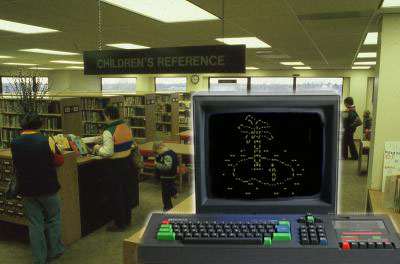

Mary thought about Lilah’s difficulties the past few months. She’d remained inflexible in her rejection of the electronic catalog and grieved for the card catalog that had now been removed. On top of that, the hated electronic wonders had exposed her cache of new books that she held to scrutinize for objectionable material before placing them on the shelves. But with the catalogs showing status as “available” once new items had been processed, there had been some patron complaints about not finding these items on the shelf. Mr. Chesterton caught on and told Lilah that keeping such a large number of books out of circulation was simply unacceptable.

With so many stresses, Lilah could not be denied. And so in North Carolina, on a balmy July evening, Mary found herself strolling the beach with Lilah when they came upon a group of students partying in the glow of a bonfire. Rolling Stones music pulsated from a boom box, competing with the roar of the surf. Grinding his hips and snapping his fingers, a skinny guy with shoulder-length hair gave a wolf whistle and pretended to leer at them.

“Hey mamas, wanna dance?”

Mary stared straight ahead rigidly, but moments later, she became aware that Lilah had slipped from her side and stepped into the circle of light. Mary watched in disbelief as her partner began gyrating her apple-shaped body. Lilah — her bulges ill-concealed by a loose multicolored, terrycloth wrap over a fuchsia bathing suit — moved with a peculiar grace.

The group, stunned by the unexpected brazenness of this plump, middle-aged stranger, wavered between derision and embarrassment. But abruptly, as though simultaneously affected by an ocean breeze, they relaxed and began clapping and laughing in approval. Lilah was a high priestess who’d joined the natives in a ritual.

After a few seconds, she stepped blithely out of the circle, gave a mocking curtsy and rejoined Mary in their stroll. The boy who had first called out hurried after them. Mary feared harassment, but he just laughed drunkenly and pressed icy Budweisers into their hands. He called Lilah a “cool old lady” and, still laughing, returned to the party.

Later, Lilah lightly dismissed the incident. It was just a silly thing she felt like doing, she said, and she refused to talk about it anymore.

Mary was left to dwell in silence on its meaning, to try to reconcile the writhing creature in firelight with the censorious mate she lived with in Irving. The incident both intrigued and unsettled her. It gave her partner a dimension that she could not fathom, a mysterious, exotic quality. Trying to capture the moment in poetry, she gravitated toward images of primitive, tribal rituals — voodoo and witchcraft. Mary regarded superstition as a weakness of the intellect but, nevertheless, could not shake the feeling that a spell had been cast.

A month passed, and Lilah seemed in good spirits at work. Mary decided that her misgivings were the product of an overwrought poetic imagination. Then, Mr. Chesterton called Lilah into his office and asked why there had been no progress in getting the backlog of books into circulation. To which Lilah replied that she’d just been too busy since returning from two weeks’ vacation. To which Mr. Chesterton replied that, yes, he realized she’d been gone on vacation, but this project was a priority with him. In a dictatorial tone, he stated that she should set aside some time each morning and get it done in two weeks. Lilah summoned all the dignity her bulk would allow and marched out.

At mid-morning break, Mary found her in in the midst of her basement cache, vigorously slamming books from one set of shelves to another three feet away.

“That man,” shrilled Lilah, “doesn’t know …” But Mary quickly signaled caution with a raised finger, as a Technical Services staff member entered the room. Then, she talked quietly for several minutes trying to soothe Lilah.