Page 1 Page 2

“Fend for himself?” I gestured at the small boy hunched on the corridor floor nearby. “Madame, a child that age cannot fend for himself.”

I guessed the boy to be around seven. He was dressed in grimy shorts and a faded T-shirt. His bare feet were covered in dust; tear tracks ran down his grubby cheeks.

“Welcome to Zaire, Dr Finmore.” Nurse Kulungu shrugged. She glanced down at her wrist watch. Her shift had just ended. “It isn’t right, but it happens all the time.”

A bead of sweat trickled down my back. The top half of the open galleries that enclosed the single-story, box-like structure of Kikwit General Hospital were open to the air. But there wasn’t much of it. And the effect of any wayward breezes that did find their way in was offset by the rusted tin roof of the hospital that absorbed the direct heat of the sun. Enormous raffia palm trees surrounded the building. Their fronds hung limp in the sweltering heat. They gave no shade.

I wished momentarily for air conditioning, then immediately felt guilty at the thought — dreaming of air conditioning in a hospital that was lucky to have a few hours of electricity a day.

“But doesn’t he have family that can take him in?” A buzzing mosquito landed on my arm. I slapped it dead; its flattened corpse left a bloody spot. I fished a tissue from my pocket and wiped it off.

“Peut-être, but no one’s come forward, and he says there was only his Mama.”

“How long has he been here?” I asked.

“A week maybe? The mother was one of the last victims.”

“And the father?”

Again the shrug. “Who knows? Dead himself most likely.”

“But how does the boy live? Where is he getting food?” After all I’d seen in Zaire, I don’t know why the plight of this one little boy was bothering me so much. But maybe it was just that; it was because of what I’d seen and didn’t want to see anymore. No more suffering. Enough. Please God, enough. I didn’t want to think about a little boy wandering the streets, snatched up by soldiers, or languishing in an orphanage, unloved.

“Hospital staff have been giving him food. A little fufu, some kwanga — not much, but enough to live.” Fufu — the local staple — was a type of paste and kwanga a type of fermented bread.

“What about the Catholic Church?” I didn’t want to see him in an orphanage, but it was better than shantytown streets… or soldiers.

“Doctor, you know as well as I do, they’ve been more occupied with the dead lately then the living.” The nurse began kneading the bridge of her nose between her thumb and index finger.

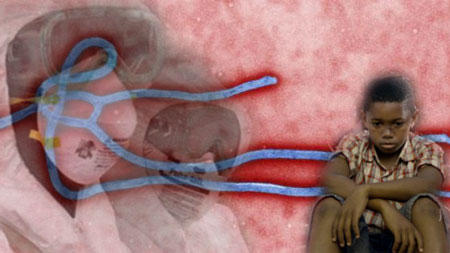

She had a point. It was the Catholic Church and the International Red Cross who had organized the mass burials of victims during the height of the epidemic. Orange corpse-filled dump trucks had rumbled down the dirt streets of Kikwit,Zaire. Ebola victims dying faster than international rescue workers could bury then. That was in May. Despite the heat, I shivered at the thought.

Now — three months later — it seemed the epidemic was finally over. I fought the urge to knock on wood.

“Well, could he not stay with you or some other staff member for a little while?” As soon as I said it, I knew I’d made a mistake.

Nurse Kulungu froze. Birds twittered in the trees outside, a motor bike putt-putted up the road, somewhere in the hospital a door slammed. She lifted her head. Blood-shot eyes looked directly into mine. She paused before replying, “Ecoutez, Doctor. My own family is still afraid to touch me. My neighbors will not even speak to me. The people think Ebola came from us, the medical personnel in this hospital. And I have not been paid in months, Doctor. In months. I have done what I can, because I care; my colleagues have given their lives. I have done all I can do, Doctor. Perhaps you ought to ask yourself what you can do for this boy, n’est-ce pas?”

She turned to leave, and I moved to stop her. “Wait, please. I’m sorry; that was stupid of me.” I touched her arm. She stopped but would not meet my eyes.

Twenty-six of the 244 victims who died in this latest battle against Ebola Zaire — a deadly biosafety level 4 virus — were medical staff. Before Médecins Sans Frontières and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention personnel arrived on the scene, local staff had been caring for Ebola victims without any protective gowns, gloves, or masks — not even rubber gloves for surgery — in a hospital without electricity and running water. To top it all off, Zaire’s civil unrest left Kikwit General medical personnel working unpaid — wars and killing people being more of a governmental and rebel priority than healing them.

I took her hand. It was dry and scaly from repeated washing. “I really am sorry.”

“It’s okay.” She withdrew her hand and rubbed it across her forehead. Her shoulders sagged. “Don’t you think I would do something if I could, Doctor?”

“I know. I know you would.” I laid a hand on the woman’s shoulder. “Let me see what I can do.”

She nodded and started to walk away. “Good luck,” she shot back over her shoulder. “We’ve tried to move him. He won’t go.”

“Oh and Nurse —?” She stopped but didn’t turn around. “— what language does he speak?” With over 200 languages spoken in Zaire, one could never be sure.

“Kituba, with the usual spattering of French.”

“And his name?”

“Christ.”

“As in Jésus Christ?” In French it sounded like “Creest.”

She laughed. “No, just Christ, Christ Nkembo.”

* * *

Page 1 Page 2

Pages: 1 2

Congratulations Shani. I’ve enjoyed reading this version of it. A moving story and took me back to the period of the ebola epidemic in that country.

Love it and u are fantabulous at everything!!

Such a moving story. I really enjoyed reading it. I look forward to reading more from this author.

What a heart warming beautiful story about compassion in a time of desperate need, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this story and would love if it became a novel!