Page 1 Page 2

Donnie hovered on a cloud of cautious optimism for days after seeing the wished-for house, and though his parents would not commit to it, he could feel them swaying some when he lobbied for its purchase. It was as if they were making room for his words in their heads, and he felt like this was real progress, considering how they usually did things — without benefit of much thought at all. But then, not surprisingly, really, the bulk of the inheritance was suddenly lost, and so the plan for the house was finished for good. The money was spent in one afternoon at a dog track near Kittery, Maine. Donnie’s father and mother weren’t even gamblers. In fact, it was their first trip to a track of any kind. Some might call this the ironic part. They told Donnie they had only traveled there as a sort of lark. His mother said she sympathized with the weary-looking, emaciated greyhounds, even as she bet the dead uncle’s money on them.

They decided that Donnie should be told the truth immediately, because it was only fair to tell him and also because, given his stubborn nature, he might have gone on forever about the house if he didn’t realize its purchase was no longer even a remote possibility. This discouraging confession took place in the living room of the apartment as Donnie was folding his bed back into the sofa. It was a Saturday morning in July. Thomas and Nathan were already out somewhere on that hot, cloudless day, running around town in their random and wild manner, courting mischief and danger — which as it turned out would remain the themes of both their lives.

“Isn’t it better, Donnie,” his father gently asked after breaking the news, “to lose a house you never had in the first place, than to have it taken away by a bank later on when you fall behind on the mortgage payments?”

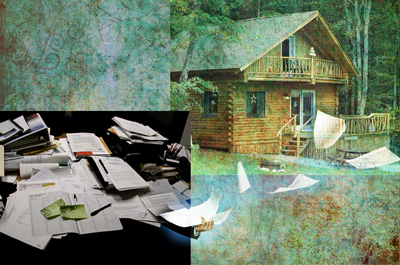

Donnie thought about this for a moment, about the cottage surrounded by the pine trees. He thought about its brick fireplace and its three real bedrooms, the rickety screened porch and its ordinary riches.

“No,” he said finally. “No, I don’t fucking believe that to be better at all, and neither should you!”

Donnie could feel a charge of adrenaline twitching through him, as if he were short-circuiting. He wanted to flee the apartment and holler down the street like his brothers often did — but to go and not come back at all. He crossed to the kitchen instead. In a single, deliberate motion, he went to the stacks on the desk, took great armfuls of his mother’s cat poems and his father’s annotated war documents and flung everything out the open window next to the stove. Then he stuck his head out too and surveyed the journey. They lived on the third floor, and Donnie watched as some of the pages were caught in a surprising updraft, wafting and soaring like strange, flat birds.

The world was suddenly a fine place for the first time maybe ever. Donnie could feel his father and mother advancing on him as the pages scattered along the alley below. He could sense the heat of their anger and shock over what he’d just done. But before they reached him and took hold, he felt something else, too — already their forgiveness and unconditional love. This would be the part of the story that Donnie would eventually remember best, long after he’d grown up and left the town and was living another kind of life entirely, quite far from home.

Page 1 Page 2

Pages: 1 2