Ann Marie pulls yet another exam from the stack of ungraded tests and glances over the multiple choice answer sheet. The Scantron machine has marked only a single incorrect answer. She flips over to the short answer portion of the test and reads: “#51: Explain, in several sentences, the relationship between friction and heat.” The response, in sloppy scrawl, reads: Friction is a force that opposes movement. Ann Marie recognizes the phrase: the exact wording from the textbook. At least someone is doing the reading. Ann Marie looks up for a moment, rolls her neck until it pops. Two-hundred-and-six tests in total. Just a few more, and she’ll be halfway.

She scans the remainder of the short answer response:

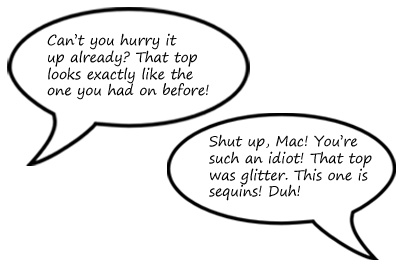

For example, when I want to get in the car and move toward the movie theater so we don’t miss all the previews, my girlfriend opposes this motion by taking a ridiculous amount of time to get ready. This causes friction, which takes the form of an argument.

Here, thought bubbles are doodled in the margins:

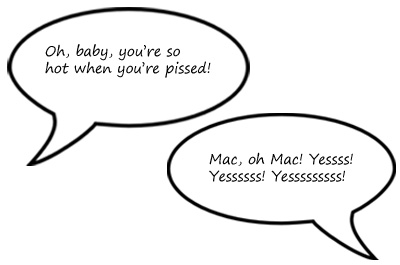

His answer continues: Friction converts useful energy (kinetic energy i.e. movement) into heat. For example, the friction of arguing impedes our movement towards the movies, but also creates heat.

Ann Marie closes her eyes for a long moment. When she opens them, the test, transliterated sex noises and all, is still on her desk.

Great. Wonderful. Fabulous. Just what she needs at 11 p.m. on a Friday night.

Ann Marie flips the test over and finds the full name of the offender: Mac Allen. She can match a face to the name instantly; the smartasses are always easy to remember.

He sits in the back row of her 3 o’clock Tuesday/Thursday lecture. Mac Allen. He’s got that lazy frat boy grin and enjoys the occasional mid-class siesta. But he speaks up sometimes, too. And even if he’s just cracking jokes, at least it breaks things up a bit. Anything was welcome to interrupt the silence of all those rows upon rows of timid undergraduates, snug in their auditorium seating.

Ann Marie flips back and reads #51 again. Technically, it’s a right answer. Ann Marie shakes her head. She never would’ve dared to do anything like this on a test. And she’s willing to bet Mac wouldn’t have either if the class were taught by a male professor.

Maybe she should just ignore it, not give him the satisfaction of getting a rise out of her. But maybe, if she doesn’t correct his inappropriate behavior, doesn’t dole out consequences for his obvious lack of respect, he’ll take it as permission to push the envelope further. What if he catcalls his French professor next? Or hits on his Calculus T.A.?

But maybe the French teacher can take it up for herself. Maybe the Calculus T.A. needs to develop a thick skin, learn how to handle students like Mac before getting too deep into an academic career of her own.

Ann Marie closes her eyes again, puts her head down on her desk. She can’t help but imagine what Mac is doing right now: out on the town, several beers deep, flipping quarters into pint glasses, laughing too loud. He’s probably planning a “trip to the movies” with his little girlfriend later.

And here she is: the only one left in the rabbit warren of professor’s offices, her own cinderblock cell so silent that she can hear each individual tick of the clock, can hear the low buzz of the fluorescent lights overhead.

How did she get here? A year ago her doctoral robes were still on backorder. On a Friday night she would’ve been in some bar with Phillip and Raami, linked arm-in-arm, singing some song about “three sheets to the wind” at the top of her lungs.

Back then, teaching intro-level undergrad courses had been a strictly slave-labor-for-tuition-waiver arrangement. Sure, there had been long nights of marathon grading, but back then all the lowly graduate students had shared an office. There had been Red Bull and Thai takeout, and every so often somebody would read aloud an excruciatingly bad student answer, eliciting groans and nods of commiseration. And when they’d finally called it a night, they’d moved as a pack to the nearest bar: a schmaltzy Irish pub that looked about as authentic as a TGIFridays. They’d sipped dark beer and bitched about their worst students and their even worse supervising professors, all puffed up with pomp and circumstance.