Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9

Connie rocked back and forth on the faded velvet sofa in her sister Lois’s living room. It was summer, 1940.

“Maybe you’re wrong,” Lois said.

“I missed twice. I never missed before.”

“You might just be nervous, the wedding coming and all,” Lois said.

“I threw up yesterday.”

“See there? Could be nerves.”

Connie reached over and clutched Lois’s arm. “Tell me what to do.”

Lois was a married lady, her big sister. She’d know.

“Have you told George?”

Connie shook her head.

Lois pulled her sister close and kissed her damp cheek. “Good. Wait ‘til after the wedding. Then tell him.”

“Why?”

“Just say the baby’s premature. He won’t know the difference.”

Connie’s head jerked up. “It’s his!”

Lois smiled. “Of course it’s his. But if he doesn’t know now, he’ll back up your story when the baby comes early.”

“It’s not George I’m worried about. It’s Papa.”

“How’s he going to know?”

“Same way everybody will. All those old ladies at the church, counting the months on their fingers. Big fat baby coming out premature? Uh-huh!”

Lois nodded.

Connie wiped her nose. “I’m scared of Papa.”

“Yeah, I know. But what’s the worst he can do?”

“Disown me.”

“He would never. You’re his favorite.”

“I wouldn’t be if he knew. He’d look at me so disappointed. And he wouldn’t love me anymore. That’s the part I couldn’t bear.”

Lois thought a minute. “You could get married early,” she finally said. “Next week, say. Tell people you and George just don’t want a big wedding.”

“I can’t. My dress is paid for. The reception’s all planned. They’d start asking questions. Besides, the baby would be coming way too early, no matter when I get married.”

“I think you should see a doctor. Make sure you’re right about this.”

“I am sure.”

“You never know. One time when I thought I was pregnant, I made an appointment with a doctor in Stanton.”

“Really? What happened?”

“My period was late, that was all.”

“Were you married?”

Lois shook her head.

Connie stared at her big sister.

“What would you have done if you were . . . ?” she asked.

“I would probably have gotten a doctor to help me.”

“Help you do what?”

“I don’t know. It didn’t happen.”

“But it’s happening to me.” Connie was crying.

“Maybe. We need to find out for sure. But if so, I’d advise you to have the baby.”

“Papa would be so ashamed.”

“Oh sweetie,” Lois moaned, holding Connie tight, rocking her on the velvet sofa.

~~~

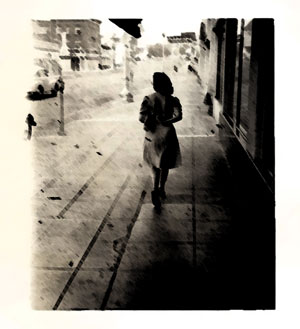

She’d met him in the spring, May 12, 1939, to be exact, when she was still sixteen. He’d come from Ringgold, Virginia, looking to set up a business. She didn’t know why he picked her, he was so much older and smarter. And he had that dimple in his chin and he was so tall. Her Papa was Tabernacle Baptist and too strict to let her go out with him, so he visited her at home, on the front porch.

“You still a baby,” her papa said. “You got no business with a man like that.”

They lived in Goldfield, North Carolina, on the small tobacco farm her papa, Walton Reynolds, Jr., had inherited from his papa. Times being hard, all the children from five on up worked on the land, summers and after school, picking tobacco, milking the three cows, feeding the chickens. Connie was the last child of six. The seventh had died, taking her mother with her.

Three months they sat out there, Connie pumping herself back and forth on the white wooden swing. George sitting opposite on a wicker chair, cooling himself with a fan from the funeral home, talking about his future.

Every twenty minutes or so, her papa would come out on the porch, make some comment about the weather, check his watch, and head back in. Then around nine o’clock, he’d announce, “Bedtime for this little girl.” And George would disappear into the twilight of a long summer day.

Meanwhile, he talked and he talked. About his plan to save up the money he was making at the hardware store so he could set himself up in business.

“This town is ready for a proper shoe store,” he’d tell her. “Everybody orders their shoes from Sears Roebuck, you know that. And they don’t fit good. Men out in the fields, they need good-fitting shoes. When I get my store, they can come in and try on as many pairs as they like ‘til they find one that fits perfect. Women, too. I can stock pretty shoes, prettier than anything you see in the catalogue. Not to mention that cheap trash they sell in the general store.”

She loved to hear him talk. About securing a loan from the bank and checking out storefronts for rent and negotiating deals with boot merchandizers. She couldn’t imagine how he knew so much. After a while, he started using we and our when he talked, as in “you’ll sell the ladies their spectator pumps and I’ll man the register.”

By the end of the year, Connie’s papa had agreed she could marry George so long as they waited until she finished high school. And that would be in June.

After the announcement in the local weekly at Christmas, her papa started letting her go out with George on Sundays after church. They’d take off in his black Ford coupe to visit friends or stop by an open field to spread a blanket and eat deviled eggs and ham biscuits. It was March when he kissed her for the first time. Sunny and warm, white apple blossoms blooming early, new grass smelling fresh.

“Come here,” George said. He was lying down on his side. Connie sat down on the blanket beside him and began opening the picnic basket.

“No. Here, with me,” he said and pulled her down beside him so they were lying face to face. Connie’s first thought was her papa, how he would say, Pick yourself up right now and go home. But she found she couldn’t move. She was staring into George’s eyes, which seemed darker than she remembered. She tried not to notice his arm heavy on her waist, his fingers somewhere, his breath on her cheek. And he was pulling her, closer and closer, so that her breasts were touching his chest. She reached out automatically to push him away. And that’s when he did it. He put his hand on the back of her head and kissed her. On the mouth. She felt herself moving closer, like something outside her was in charge. Then she was kissing him and her hand was feeling the soft skin under his shirt. He stopped it that time, pulled himself up, and said, “Get out the picnic, honey,” in a hoarse voice she hadn’t heard before.

After that, every time they took a drive, she would tell herself, I’m not gonna do it, not this time. She would not lie down beside him, she would not let him kiss her, it was a sin to even want to. And in the car, on the way, it seemed so easy, saying no. But then he would stop the car. And she would follow him and let him pull her down, down onto the blanket, down against his hard chest, and she would feel herself melting into him. Feel that place somewhere low in her body come alive. He stopped it the next time and the next. Until he couldn’t.

(continued on page 2)

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9