(1951-1981)

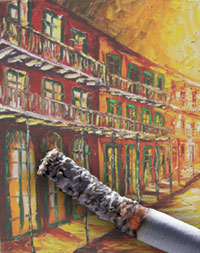

In the early part of an evening of our lives, my brother and I felt like we were trapped in a net made of glue. New Orleans humidity was the same as the temperature: ninety. After we drank some cheap wine, I noticed he had drifted off to sleep with ashes hanging from fifty percent of his cigarette. The breeze coming from the window was cool; he sneezed. I went to cover him with a blanket, and of course, put the cigarette out, but the ashes fell to the floor and dissipated at the wind’s command. I threw the blanket over him, put what was left of his ashed cigarette in the ashtray, then went to sleep.

I was sixteen. He was two years less but more curious. He was the one who found a way to get into our house without a key, camouflage Mrs. Katy’s lemon pies until they “disappeared,” and find someone old enough to purchase wine for us. But on the other hand, I soon proved to be a partner in his mischief. I mastered all his antics.

He was good in biology, being the first to explain to me the process of photosynthesis. I was a wiz in mathematics, mentally computing what our change should be before the grocer added it up on the cash register. We supplemented each other perfectly. My brother and I did practically everything together. We went to school, church, parties, fishing, swimming. We played ball together, and to secure our togetherness even more, we dated sisters.

Years later, in the latest part of an evening of my life, I sat staring across the room, after drinking a bottle of Don Pernignon champagne. I noticed that the breeze had become wild and colder, but this time it did not interfere with my brother or his ashes, for they both were resting well in the hermetically sealed urn on my altar.