|

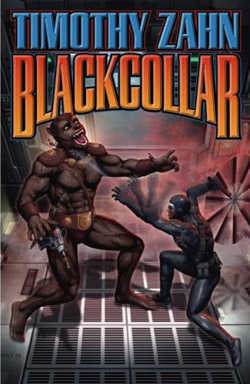

David Mattingly(continued) Interview by Alyce Wilson What is important to you in your art? What do you hope to achieve? Between now and the time I die, I hope I do a whole bunch more paintings, and I hope I change and produce some fresh things. I guess my one real desire is to keep working going up into old age. I've always admired guys that get up and do it every morning. And not necessarily agonize over where the state of their career is at any given moment. I admired Chesley Bonestell, who painted until he was, like, 100 years old. And the last 10 years of his work, none of it's all that good. But I just love the fact that the guy still loved it so much that he got up and he did it. But I guess it's hard for me to define any overarching goals, because the changes that have taken place in my style over time have largely just been sort of an evolutionary process. Very rarely do I wake up and suddenly find something has changed a lot. You just sort of experiment and learn more as you do it more. And that's how a change will come in your style. I think my style is substantially different than it was 10 years ago, so it definitely has changed. But exactly why that changed, it wasn't something I really consciously thought about. What about with an individual work? Working on, say, the new Honor Harrington novel, what do you set as your goal in an individual work? What's important to you to get across? I had a great teacher in art school, and he said there's three stages to a project. The first stage is you get it, you're all excited about it, and you say, "I'm going to make this the best thing I possibly can do. The second stage is you get into it, and you discover it's probably not going to be the best thing you can possibly do. And then the third stage is finishing it up anyway and making it the very best project you possibly can. I mean, my goal when I started At All Costs was, No. 1, I love David Web's work. I know these are important books to my publisher. And if anything, I was more motivated to make the very best cover I possibly could. Some factors are uncontrollable. You can't ever sit down and say, "This is it. This next cover has to be the best one I've ever done." You could put more time and more effort into it. Hopefully, if it's not turning out, the effort can help bring it up a little bit. Or if you can put less time into it, and the entire effort will sag. My goal was to produce something that would really knock it out of the park. It generally is that all the time. I certainly never go into it and say, "This is my chance to do a mediocre cover." But I mean the Honor cover, I thought turned out reasonably well. When David talked to me about having Honor holding a baby, my main concern was, there's got to be something else there besides Honor holding a baby. And that's why we've got Nimitz playing with the baby with the medal. And then I brought in the space battle in the background to just remind people: "Don't worry. It's not just going to be Honor hanging out with her baby. She's going to go out there, and she's going to kick some ass, and there's going to be some gigantic space battles and all that." And so, it was essentially my desire to go ahead and give them the softer Honor with the baby but also remind them that it's still going to be really an exciting piece. What would you say to beginning artists? What advice would you give them? My advice would be get in the very best art school you can, and while you're in art school, work as hard as you possibly can. Don't party. Don't do anything else. Art school is the most important time you'll ever have in your life, and if you've gotten into a good, strict art school, learn as much as you can. It's really hard to ever go back and get that time. For the most part, although I work completely on the computer myself, I'd say stay away from the computer as long as you possibly can. Try and pick up the skills of drawing and painting, all of which will directly apply to your later work, regardless of the medium. But if you get involved with the computer right away, you can fail to learn those tools, so it will really be essential along the way. But I would say, for the most part, that the art school experience, for me, is what allowed me to work as a professional all these years. If I hadn't gone to art school, it never would have happened. But I needed that time in art school. I went to a really fine art school called Art Center College of Design. And their attitude and the level of professionalism was what got me to where I am today. I'm teaching in the School of Visual Arts in New York, which is a very good school, one day a week. And we do see kids that are not giving it their total effort. And if you're not giving your total effort, you're not going to work as a professional artist. You're going to be doing something else four years from now. So, you've got to ask yourself how badly do you want it? And if you really want it, every single one of those classes you need to ace. What's coming up for you? What do you have in the works? I'm doing a second book in Tim Zahn's Blackcollar series. I'm using sort of a weird technique that I haven't seen used a lot, and that's showing multiple images of the figure in motion. The Blackcollar are sort of futuristic warriors, and this guy is swinging a numchuck and it shows multiple images of the numchuck. And then he's throwing a star, and you actually see five images of his arm as he throws. And then the second cover is going to sort of extend that technique. It's something I'm kind of interested in. I've seen it in comics a lot, but you don't see it in cover imagery very much. And it's something I'd like to explore a little more. This is an example of an evolutionary change. Comic books are a huge influence on me. And I've looked at — I've looked at guys who have done it, especially Jim Steranko, who would do these multiple image things. And yet you don't see it in realistic covers very much. So it's something I'd like to try and work on in the future. And also my lenticular screens are a great love. Lenticular screens, how do you do them? It's a lens that's placed over specially prepared prints. And the print actually, you make eight different images of a scene, with the background and the foreground multiplying against each other. And then you cut these images into little strips. And then you put this lens over the top of the strips, and what the lens does is it only shows one little strip of the image to your eye at a time. So as you move back and forth, actually, it looks as though you're getting a 3D image of the piece. And I actually do them at home. I don't send them out to a printer or anything. I do it from start to finish at my home. And I've been showing them at conventions. So I certainly would love a client who would use it on a package. But they're expensive. And so it's got to be the sort of appropriate project that people would be willing to pay an extra 50 cents or an extra dollar on their package to have the lenticular cover. I guess that's another stage of the hyperrealism. Where's it's possible, the third dimension. 3D stuff I really love. When I pass by a lenticular screen by someone else, it's like I have to look at it and analyze how they've done it and all that. David Mattingly's latest painting commemorates publisher Jim Baen, who died in 2006. You can view the work at David's site. Many more examples of his paintings, including his animation, can also be viewed there. This interview was edited for length and clarity. |