|

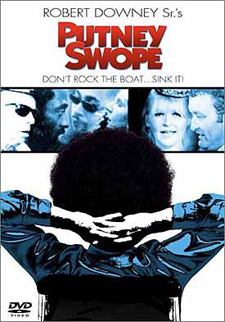

Robert Downey Sr.(continued) Interview by Alyce Wilson So let's talk more about what your process is for a film. Does it start first with a fresh idea, or does it start first with maybe a theme in your head? They're all different. When I did the first ones (ph), I did all of them myself. Now I'm writing on my own again. I'm enjoying it. Everything's different. I don't know how it happens. Are those your favorite films, the ones that you yourself wrote? Yes, basically. Actually, one of the best things I've ever done somebody else wrote. It was a television special called Sticks and Bones with Joe Papp in New York. He had seen the film Greaser's Palace and asked me to direct a television special for Shakespeare. Yes, because he started the [New York] Shakespeare festival. What was the film about? He had this playwright, David Rabe, and he asked me if I could make a visual presentation of this play. So we took an hour out of it. And moved it around a little bit and made something out of it. And it had so much impact that they threw it off the air. It was about a returning POW from Vietnam. And it has gone back on the air without commercials on CBS. That was later. And then they had a nice audience. That was very good television. But I didn't write that. All I did was tighten it and visualize it. Adapt it. Yes. For television. And that was fun to do something like that, especially with no commercials on a network. Do you have a Philadelphia connection, other than Max? No. Because it seems like the Philadelphia Film Fest has really embraced you. They've been great. And I wasn't sure if it was because of Rittenhouse Square or if it went back earlier than that. No. TLA at one time used to show my films. Back in the '70s. They've been very good to be. They've been — because if nobody shows up, they don't hold it against me. We've had some big crowds for some of the documentaries. They've had to actually add screens for that. Rittenhouse Square. And Strut did very well. Yes, I could imagine. That would be a fun movie to do. Yes, it was fun. I mean, I came in late. I basically did a lot of the edits, but I came in late to that. And had a great time. Tell me more about efforts to preserve your films. I know with Pound, your wife Rosemary [Rogers] was really instrumental in pushing you to preserve that. Tell me more about how that came about. Well, it's just difficult because everything now is preserved because it's digital. Back then it was too cumbersome to think about it. And suddenly, they were disappearing. So it's hard. It's hard to figure it out. In a way, it's good, because it will liberate you from the past. You don't go back. You look at other things. But I'm happy to be alive, so whatever happens. And you have a new DVD coming out of Putney Swope? New DVD of it is coming out soon by Image, which is Criterion. Is that a restored version? No, it's the same one, only with — there's one thing where they showed me the movie and I made a commentary about what happened in every shot. It's kind of funny. And then an interview of me from the old DVD. Putney Swope is one of your more critically acclaimed. Well, it had distribution. Unlike most. Almost didn't. Nobody wanted it. And then the man who owned all the theaters in New York, and he was distributing films. Cinema Five, which was great. "I don't understand your movie, but I like it. Let's open it up." And he opened it right away and had an audience around the country. But that was luck. I actually put it on a shelf and said, "Forget this one. Nobody wants it." Because I was thinking that one of the reasons that film did well — I didn't know of the distribution story — but because it coincided with the cultural zeitgeist of the time. It could. It could be. The Civil Rights Movement. And a lot of experimental things that people were starting to come out with. That came out the same week as Easy Rider. So two of the films, mine on a tiny level, but both films became like the Sixties, whatever. Yes. I like the whole idea of "Don't rock the boat, sink it." But then he kind of becomes the boat. Right. So tell me more about the making of that movie and what went into that one. What was your inspiration for that one? I was working with a black guy in a place that we were in a little offshoot of the department of a production company, and the guy who ran it was a very adventuresome guy, and he had seen one of my films in the village and asked me to join the company as an experimental — made mostly, I think, commercials, but he wanted to do more. And the black guy said to me — I forget exactly how he knew, but he said, you know, "We do the same kind of work but you make more money than I do." I said, "Well, let's go see Bob, the boss." With him. He gave me that logic: "If I give him a raise, I have to give you a raise, and we're right back where we started." I don't know what his joke was, but that — so that's enough for me. I started thinking about a movie. And plus I just thought advertising was so ridiculous. What sort of a reaction did you get from different circles in that, other than critics? Well, it was extreme, both worlds. You mean, both for and against? Exactly. I remember I went to Boston, and I went to Roxbury to be interviewed up there. It's a black area. The guy thought I was going to be black, and he was not a happy guy. Another film from the '70s that took some really kind of interesting approaches to some big ideas is Greaser's Palace. It's almost like a bawdier version of Godspell or one of those movies that looks at the Christ story from another point of view. You've got some visual images in that that are just astounding, like you have this guy standing there holding a painting of the Last Supper next to a scene that's going on, and it's as if he's not even there. Nobody sees him; nobody acknowledges him. But it's as if you're saying, "By the way, if you wondered if this was a Christ story, look there." That's good. That's good. That's exactly the thinking. What went into your creative process for that film? How did you come up with that one? I just decided that that was the next one. A woman with a rich husband approached me and said to me, "I'd like to make a film with you, and I have access (ph)." So I wrote it. The lead actor [Allan Arbus] looks so much like Gene Wilder. Do you know who that is? On the television show M*A*S*H, he was the psychiatrist. You're right. But with shorter hair. He's been around. He's Diane Arbus' — the photographer, that's her husband. She killed herself while we were making Greaser's Palace. They were divorced. Now there's a movie coming out about her with my son in it. Which movie is that? It's called Fur. I've heard of that. That must have been — did that throw off the production at all? It's kind of a selfish question, but... Yes, for about a week. Yes, it was — he had to leave, and — I never knew her. He was great. He's in Putney Swope, too. Same guy. He plays the guy who keeps giving Putney bad news. Again, the singing and dancing comes into [Greaser's Palace], too. Would you do a full-blown musical? I'm doing one now, on Kurt Weill. OK. But that is a documentary. But it's a musical, because it's loaded with music. This is the most music I've ever had, the one on Kurt Weill. It's about a musician, so how could you not? And a lot of it's already on film and tape. Tony Bennett, Marianne Faithful. We've got a lot of stuff. That's going to be a soundtrack that's going to kick off too, huh? I hope so.

|