PROBE

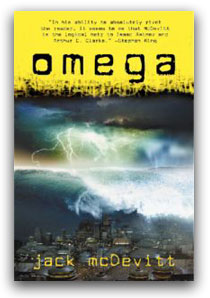

Jack McDevitt

(continued)

Interview by Alyce Wilson

What's been the response to Omega, [your latest book]?

As far as I know, it's positive. Nobody has blown it up yet. The Washington Post had an enthusiastic review. I know I get... there's a rave review coming up in the Florida Times. And my wife called me yesterday to tell me that there's a strong review in Locus. And there have been a couple of reviews on the web that were positive.

But you know, sometimes I get accused of being retro. And there was one reviewer who — this is for an earlier book — suggested I should get the Hugo for 1954, but that's all right.

I was accused by one guy of writing [Robert] Heinlein. I can live with that.

What would your advice be to a writer today? Not just a science fiction

writer but any writer?

Read everything in sight. Read widely. Read novels, read science, read biography, history, you name it. I think that, generally, anybody who's successful in writing has already acquired a passion and is probably already doing that. So you know, that's a given.

And I think it should be true that they are observers of the human scene. And that should be a given.

So maybe what we're really asking is, what makes for a good narrative? And I'm not sure what the magic is for that. It's instinctive, and I'm not sure that it's something that can be learned.

I've often thought that one of the early indicators of whether or not you can succeed as a professional writer is whether you can deliver a good punch line.

A good punch line? How do you mean that?

You know how to end a story or a joke or whatever, and you make your statement and then move on.

I've known people who will start telling me about their relatives, and I think they're getting to a funny line. And it goes on and on and never stops. Anybody that does that obviously should not be in the business.

But it's an ability to manipulate language to deliver a punch. You need to be able to do that.

I was listening to some people the other day who were complaining that when they submit stories to the magazines, the editors don't give them any advice. The editors just send back a standard rejection and don't tell them what's wrong with the story. And editors, of course, are not able to do that. They get too much.

And there's a famous story of somebody who — I suppose this happened at a national seminar — where somebody said, "Dr. Asimov, I sent a story to your magazine, and I put a paperclip or stapled all the pages together or something. They refused it; they rejected it. When it came back, the paperclip was still in place. They never read the story."

To which Dr. Asimov had responded, "You don't have to eat the whole egg to know that it's rotten."

People who are established writers probably don't need advice from somebody like me. They've succeeded; they're doing fine. Anything I tell them is probably going to screw them up.

People who want to break through as a writer need to realize that's their responsibility when they submit a story.

Now, novels are a little bit different. But if there is a story, it's their responsibility to write an opening paragraph that grabs the editor by the throat and, at that point, prevents the editor from ever putting the thing down again. If they can't do that, then they don't deserve to have their thing read.

That's a little harsh to say it that way but, I mean, that's the reality. The editor realizes that the reader's not going to hang in there, either. So it's the writer's responsibility to make sure that the editor reads.

Lew Shiner is one of the best story doctors I've ever known. He said one time that if you're writing a story, the story should open as close as humanly possible to the climax.

He does writing workshops. He said they always want to start with the weather report: "It was a dark and stormy night." And you start with somebody falling down a flight of stars, basically. It gets the thing off and running. And if they have to have back story, you do it on the run. Don't put it up front.

The biggest problem that writers have, if you're looking for a single major defect in writing techniques by most people trying to break into the business, I think — most editors I talk to have indicated — they overwrite. They write too much.

What's happened is — and I was one of the people responsible — English teachers give those essays where you say, at least 500 words. So did I. I figured out by about the third or fourth year I was teaching that wasn't the way to do it.

What I started doing was I'd give them piles of information, and then I'd say, "OK, you know, I want you to give me back the information in an appropriate order, set it up, no more than 300 words."

You know, learn to write good, nice, tight journalistic prose.