(continued)

By John Phillips

"How did you do it?" The noble lady clutched her daughter in frantic delight, the young girl looking all around with dark wondering eyes. "How did you raise her? What... What do I call you?"

"My name's Digger, but you must tell no one about any of this. Not

my name. Nothing." His jaw clenched, his eyes closed tight. "Please

leave..." His breathing quickened and he panted almost to the point

of speechlessness. "Before they become suspicious, before you're

seen with your child. On your horse ... leave this town ... and never

return. Her rebirth depends on it. Go ... before the Black Death

returns for her."

"Let me pay you." She rummaged through her pockets, scarcely able to just walk away from the man the spade and the miracle.

"Just go ... I beg you!"

With a look of stupid amazement on her face, the mother backed slowly away with her daughter and retreated into the mist and shadows.

The gravedigger fell flat on his face. A scorching heat blazed through

his body, but the awesome pain fed him, nourished his yearning. The hot

and maddening pain ripped at his chest like a bout of heartburn fuelled

by hellfire flames.

Digger summoned all strength and spirit as he fought viciously to roll

over, an ordeal not unlike a madman trying to worm out of a straightjacket.

He threw himself onto his back with sudden fury, and his cloak wriggled

over his legs and arms, shrouding his willowy body. The displaced soil

made a low gravelly sound as it shuffled back into the grave to blanket

the digger and his spade....

Shortly after sunset he started back for his lodgings south of the river, a seven-mile slog through several heavily quarantined parishes. With his face and hands and the patchwork cloak spotlessly clean, he came to a footbridge and crossed it with all haste, averting his eyes from a grey human shape turning in the low rolling waves.

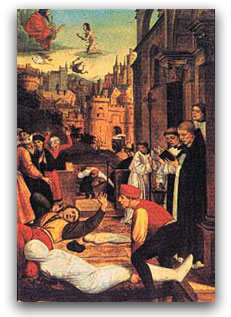

He made his way along rows of wooden houses where night watchmen guarded

the doors of those homes with red crosses painted on them. Corpses had

been dumped like bathwater into the gutters and left on the street in

a tangle of decomposing limbs. Digger saw an all too familiar sight. A

man dragged his dead wife out of the house by her feet, the woman's frayed

stockings exposing ugly black sores. Digger shuddered at the unmistakable

tolling of bellmen leading their dead-cart down the street. A few diseased

creatures straggled along behind in a kind of procession of the near dead.

Beneath a swirling cloud of black crows, they dragged their limbs and

rags as best they could, for they knew the dead-cart had but one destination.

A shrieking woman flung her door wide open and threw herself on the cart. Blood streamed from her nose, and her neck had swelled up like a loaf of bread. Bellmen tried coaxing her down but she had nestled into the corpses and lay still. Digger tugged his hood forward and turned from the gruesome sadness. He had never grown numb to it.

Odours were so thick and redolent he could taste them. The combined smells of wildly concocted medicines, the burning of juniper branches, and the stench of rotting corpses saturated the night air. And Digger could hear the grey sounds of grief everywhere. Loud wails of lament, shrieks of terror and despair, had now moved indoors. Most lived behind padlocked doors, either by force of authorities or a desire to survive. Only the dead seemed to inhabit the streets.

Entering the merchant quarter, he heard the rusty squeak of signboards

swinging in a hollow wind. Digger eyed the apothecary's sign of a mortar

and pestle hanging above the empty shop, which only days before had been

jammed with people literally dieing to buy a potion or some medicinal

brew. In truth, there was no medicine better than flight from the plagued

city. A harsher truth still: There was no cure for the disease except

death itself.

His feet ached after his long hike from the north parish cemetery. By

late evening, he arrived at the market square not far from his home. Few

shutters, if any, rattled with the closing of storefronts for the day,

and the colourful aprons of stalls no longer flowered the lonely square.

Although Digger showed no symptoms of the plague — the typical swelling

round the neck, bloody nose, or the black spotting — those who did

venture outdoors avoided him. He didn't dress like a typical gravedigger,

with his paprika red cloak, but the shovel he carried on his back marked

him as a man to be shunned. So smiles never came his way, and rarely an

eye met his.

But Digger watched them, always on the alert for the next one.

Sorrow attracted him. He felt drawn to the heartfelt grief of a mother,

or father, whose lost child had been loved as a child should be loved,

who was dearly missed, and had never been neglected or mistreated. Such

parents could be hard to find in the best of times.

His grey eyes flashed towards a peculiar noise, a kind of kissing sound, and saw a market-woman slumped hard against a crumbled brick wall. Her dull blue apron hung in pieces around her waist and the corset-like bodice had been ripped, exposing her bare shoulder and the black eyes of the pestilence.

He nudged the woman but she truly wore the rictus of death, with her jaw locked wide open and her eyes tilted back. Shaking his head, he turned for the street but again heard the strange sound.

Turning the lady over was like rolling a fallen timber. He heaved her

onto her back and saw a small grey bundle in the crook of her rigid arm.

His eyelids flared, the whites showing like full moons. The sight of a

wee infant suckling its dead mother's breast paralysed his vision —

his eyes could not budge from the horror.

Digger didn't realise he had stopped breathing till it returned in one wheezing gasp. He scooped the filthy baby up in his arms and peeled back the cloth wrapping. The same deathly spots covered the child's malnourished body.

He dropped knee by knee weeping, clutching the bundle to his chest, not

knowing what to do, where to take the breathing child, what to do with

it. Only the howling tears made sense....

He returned to the road, his arms cold and empty, and his face pitted with sorrow. Digger's footsteps fell heavily on the cobbles, jarring his soul. His pity for the mother and child would endure, even though the falling dead had become as common as the infinite dropping of leaves in the autumn. He was pained by his powerlessness.

Through the muted atmosphere of death and death to come he saw a welcoming sight. He softly closed his eyes as if they breathed a sigh of relief at the laneway up ahead, the one leading to his lodgings.

"Mister. Hoy, mister ... help me," came a faint voice.

"I'm my master's servant-maid, and he's been dead for two days."

With her tattered white sleeve hanging like tassels, she pointed down

at the doorway to the house, which a night watchman apparently guarded

while fast asleep. "He won't unlock the door and let me go, even

though I've sworn an oath I've none of the black tokens; I've examined

myself proper. Look!" She lifted her skirt and revealed parts of

herself that only a husband or physician should ever see.

"I've begged him up and down to fetch an inspector, or a chirugeon, so I could get a health certificate ..." Her watery eyes glistened in the moonlight and looked like she shed diamond tears. "I'm not infected," she blubbered, "yet it seems I must be entombed with my master. Please ... slip the keys from his belt and unlock the door."

Blood began trickling down from her nostril, but she didn't notice that the patent sign of certain death sat warmly on her upper lip.

"Do you need food or water?"

"Just my freedom." The blood spread around her mouth, and she looked like an overworked prostitute with smeared lipstick.

"I'm powerless." Digger lowered his chin. "Forgive me."

"Hoy! Come back here, you heartless worm! Don't leave me here to die!"

The watchman snorted himself awake and stumbled from the door-porch.

After dusting himself down he hollered up to the infected woman to shut

her mouth and get back inside, lest she spread the disease on the wind.

"Out the way, sir!"

Digger continued down the lane to the hovel that served as his temporary

abode. His wounded eyes wept as he came to his doorway. His last thought

before stepping from the street was for the infected baby whose suffering

he had ended....