Page 1 Page 2

His battery was posted on the left slope of Cemetery hill, without the cover of a tree or shrub to mask his position.— Guns, men and horses stood in clear relief against the sky, a target for the enemy.

His battery was in continuous action for two days.

On the afternoon of the 3d of July, the enemy turned the fearful fire of his one hundred and fifty guns upon this part of our line. Every description of missile came shrieking across the plain on its errand of death.

Cushing’s battery, at this time, was the mark for a least six full batteries of the enemy. His horses were all killed— his men falling fast around him—the ground literally paved with iron—and annihilation staring him in the face.

Once, he went to the General’s headquarters, where few were able to communicate intelligibly, and calmly asked for reinforcements. An attempt to comply with his request, proved unsuccessful, and the devoted few were left to meet the ordeal alone.

The Commander of the artillery brigade advised the brave Captain to fall back, fearing his guns would be lost. — He answered, “Let the battery go, we’ll go with it!” His men cheered him. — Not long after a large fragment of shell wounded him severely in the groin. He was urged to leave the filed, but he merely sent a sergeant for a little water with which to bathe the wound, while he went from gun to gun helping and encouraging his men. The rebel artillery fire now slackened, while dark masses of the enemy were seen emerging from the woods.

On they came in three dense columns, the veteran corps of Longstreet, Hill and Kwell, determined to pierce our line, and officers, men and horses, were drenched with rain, tired and half famished; yet Lieutenant Cushing was at once ordered to proceed with his section of artillery, supported by a regiment of infantry, eight miles towards Fairfax C.H., to meet the enemy supposed to be advancing on Washington.

He cheerfully complied, and his reconnaissance soon proved that the enemy had failed to comprehend, or was unable to improve, the advantage gained.

Lieut. Cushing’s name appears among those mentioned for gallantry in General McDowell’s official report.

When Gen. McClellan took command of and re-organized the army of the Potomac, Lieut. Cushing accepted the position of Chief of Ordinance, with the rank of Captain on Gen. Sumner’s staff. He fully shared the general confidence felt in our well disciplined army and its young commander, and started for the Peninsula buoyant with hope. In the battle of Williamsburg, he was constantly exposed to danger and had his horse shot under him. At Fair Oaks, he fought with great intrepidity by the side of his General, and was struck in the breast by a mine ball which was providentially stopped by his dispatch-book and pistol. Of this battle, he afterwards wrote—“the fight on Saturday night was the grandest sight I ever witnessed. Just as it was getting dark, the muskets were much heated, there were two long parallel sheets of flame from the opposing lines, and I can conceive of nothing more grand than the spectacle presented—nothing so exhilarating as that splendid bayonet charge. I never expect to witness another so beautiful a fight, if I live to be as old as Methuselah.”

During the seven days’ battles, he was ever conspicuous: constantly in the saddle, a number of horses dropped under him from fatigue, and one was shot under him in the battle of Glendale, which took place on the 30th of June, 1862. In that engagement, the second corps under Gen. Sumner captured a large number of prisoners and three stand of colors.

The rebel artillery are now slackened while dark masses of the enemy were seen emerging from the woods.

On they came in three dense columns, the veteran corps of Longstreet, Hill and Ewell, determined to pierce our line, and send the army of the Union routed and flying from the field. The disabled condition of Cushing’s battery, seemed to especially invite the charge. His infantry supports had fallen back before the storm of bullets that swept over the brow of the hill—three more of his guns had been rendered useless, one actually bent by the heat of his rapid firing, and he was himself again wounded, a ball passing through his arm near the shoulder. Once more he was implored to leave the field, but the calmly yet sternly refused to desert the post of duty, and continued by the side of his last gun, pouring grape and canister into the rapidly advancing rebels, hurling them back wit ha final discharge, as they reached the very muzzle of his piece; and enabling our infantry to crown the repulse with a decisive victory. At this moment, when the heroic captain was coolly examining his last wound, from which the blood was streaming, a musket ball struck him in the mouth, wounding him mortally.

He staggered, but gathered strength and said to his men—“boys, you can now do as you please; you have satisfied me, and have done more with these pieces than I expected.” He sank to the ground, and his men, the few that were left, offered immediately to remove him from the field; but he signified his desire to remain and die with his battery.—He lived but about fifteen minutes. In front of his position fell three rebel Generals; and in the charge and rout that followed the rebel repulse, the Second Corps alone captured twenty-seven battle flags.

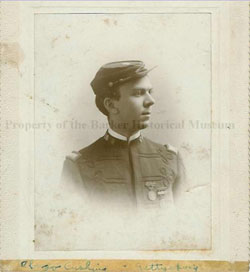

At the time of his death, Capt. Cushing was twenty-two years of age. In person, he was fully six feet high, handsomely and powerfully built, with prominent, clear blue eyes, and light brown hair.

Page 1 Page 2

Pages: 1 2