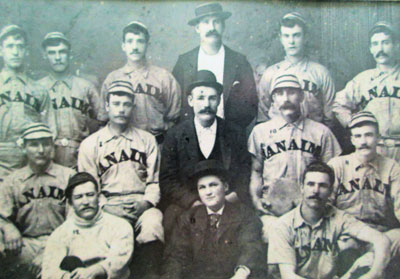

The author’s father is in the top row, to the right of the man in the hat

In late August of 1957, my father took me on a trip to visit his home town of Nanaimo in British Columbia. We stayed in the Plaza Hotel, where, almost a half century earlier, he’d been a bellhop, before going to work in the coal mines.

On our first morning, just after breakfast, my father took me on a walking tour of Nanaimo Harbor. We stopped at the Bastion, a fortress constructed in 1853 by the Hudson Bay Company to protect their coal mining interests on Vancouver Island. My father pointed out that there were no nails used, and the lumber was hand hewn with broad axes and adzes.

Too much work, I thought.

About a half block past the Bastion, an old man in a tan windbreaker, worn, black Frisco jeans, and a ball cap sat hunched on a rickety wooden bench with his back to the harbor, staring blankly at the building across the street. As we approached, he turned his face toward us, and the first thing I noticed was a broad tobacco stain on the gray stubble of his pointy chin.

Withered, age-spotted hands rested atop the brass handle of a mahogany cane planted on the sidewalk between his ratty sneakers. Large, hairy ears supported the temples of his heavy framed glasses, but behind the thick lenses were keen, pale blue eyes. My father slowed, his back stiffened, and I could tell there was an instant recognition.

The man’s eyes tapered into a squint, as he stretched his neck toward us, straining to get a closer look. His upper lip quivered, finally forming a snarl. He sat back and said, “I still remember that catch, you sonofabitch.”

My father smiled. “How’ve you been? It’s been a long time.”

The man nodded, turned toward me, and spat a long stream of brown juice onto the already heavily stained sidewalk that circled his feet.

“That your son?” he asked.

“Yes. My boy, Johnny.”

“He’s a nice-looking kid.” His snarling lip eased into a flat line. “Well, take care,” he said and dismissed us with a flick of his wrist, turning his attention back to the building across the street.

I hesitated, feeling awkward about such an abrupt dismissal by that gruff old geezer. I thought that after calling my father an S.O.B., more needed to be said, but my father gave me a wink and a quick jerk of his head, so we walked away.

After we got out of earshot, I asked, “Who was that? And why’d he call you an S.O.B.?”

Dad smiled and began telling a tale of his youth when he’d played baseball for a team with the unimaginative name of the Nanaimo Miners — young coal miners from the town of Nanaimo.

He explained how much the pride of the coal mining communities rode on the won-lost record of the previous season. If the town of Duncan had a better record than Ladysmith, it was a victory for all Duncanites, even if they didn’t win the island championship. After the season, the cry of “wait till next year” would echo up and down the island.

But even with the fierce competition, the play on the field was always fun and friendly, except when it came to the Victoria Vipers. Beating them had become an obsession, too often ending in failure.

My father said, “We hated playing them, because they’d laugh and taunt, all the while knocking the crap out of us. It happened every time we played ‘em.”

The Victoria Vipers was always the top team. Most players were barrel-chested, bearded men with arms big as tree trunks. Their roster consisted of the best players on the island laced with some players from the US. The average age of the team was 26.

Their sponsor, Timber Management of British Columbia Ltd, had plenty of money and hired the best players to work at good paying, menial jobs in their sawmill. The players had to be physically in the employment of their sponsor. This was part of the league rules.

Their manager, Adolph Bronco, was a swarthy, round, little, cigar-smoking, loudmouth prick, whose claim to fame was that he had been called up to play for the Cincinnati Red Legs. He was a third-string catcher but acted as if he were the legendary catcher Roger “The Duke of Tralee” Bresnhan.

The joke around the league was that Adolph was more of a horse’s arse than a bronco. But the underhanded tactics and style of play which he employed allowed him to keep his job year in and year out. And he did know how to win. His strong suit was intimidation. He argued, red-faced, every call that went against his team and chided other managers if they did the same.

At the end of each season, Bronco would go to the other teams and approach their star players, offering them good paying jobs with Timber Management and positions with the Vipers. On the island, playing for the Vipers was like playing for the Yankees.

But those who traded their hometown loyalty for the prestige of playing for the Vipers would be soundly booed when they returned to play against their previous team and would often be forced to leave their hometown and take up residence in Victoria, just to avoid the off-season harassing.

Attitude was a major ingredient if a player was to become a Viper. They had to be physically better and know how to psychologically get and maintain an edge on the opposing players. They employed a style of play that was beyond hardnosed, it was dirty — cheap shot dirty. Injuring a rival player brought a cheer from their bench. The opposing infielders knew if a Viper came in sliding, he’d try to rip your hand open with sharpened steel spikes.

On the other hand, if the Vipers were on defense, they would use the ball as a weapon, slamming it to your head or whacking you in the nuts. Then stand laughing at the man rolling in the dirt, while pointing to the rival dugout, trying to bait their opponents into a fight by mouthing, “You’re next.”

But generally no fight occurred. While the other team sent out a couple of players to carry their injured teammate back to the safety of the dugout, the umpires would stand clear waiting and watching for something to happen.

However, loyalty was not a trait among the Vipers management. With the Vipers, winning was everything. There was no room for batting slumps or errors. If a player had a bad season and a replacement could be pirated from another team, he would be dropped unceremoniously from the team, pulled from his cushy job and sent to the woods to be a choke setter or lumberjack.

Most ex-Vipers quit but had a hard time readjusting to life post-Vipers. They would humbly crawl back to their hometown, hoping that people would forgive, and maybe they could get their old job back.

I knew you could bring it!!! The details of a game was life itself. Good job!