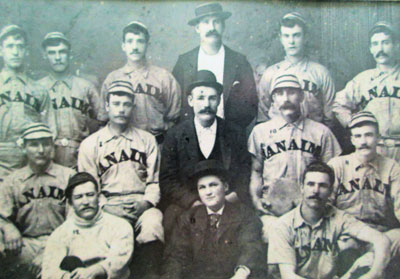

The author’s father is in the top row, to the right of the man in the hat

On the last day of the season, the Vipers’ opponents were the Nanaimo Miners, a team which consisted of mostly young, fresh-faced boys from the mines.

Jimmy Dolan, a muscular, black-haired, brown-eyed, nineteen-year-old was the Miners pitcher. He’d been the main pitcher for the past three years. Each year he’d improved and matured, but he still tried to throw too hard and had control problems. Nevertheless, he’d gotten better and was the best the Miners had.

My dad’s best pal, Jackson Whitehead, a tall slender twenty-year-old, played left field. He wasn’t the fastest player on the team, but he was a steady fielder and swung a solid stick.

Pepper Jones played third. He had lost his pinky finger on his glove hand in a freak accident involving a barbed wire fence but adjusted for the loss of the digit by stopping many a ground ball with his body, mostly his black-and-blue chest.

Bobby Thomas played first. His slim, six-foot-two physique and coarse, unkempt black hair made his cap look too small for his head. That and his wry sense of humor made him the team clown.

My dad played right field, alongside centerfielder Chester Harris. Chester was a timid boy of nineteen who stuttered and had a cannon-like arm. Though good-natured about the friendly kidding that his stammer brought, he rarely spoke unless there was something important to say.

Bobby Thomas claimed by the time Chester finished calling for the ball, he’d have already thrown it back to the infield.

To which Chester would reply, “F-f-fok y-y-youse a-a-a-arseholes!” and then smile, explaining that his stuttering was an asset, because his swearing took longer and meant much more.

My father said, “When Chester sang, he had a voice like an angel but never stuttered.”

A bitter shortstop, Mickey Mowery played without his index finger, which he had lost because the manager of the Plaza Hotel had disregarded Mickey’s safety for the convenience of a customer. My father had worked with Mickey that day and had seen him snap. Mickey was never the same. His narrow-set eyes reflected the dark brooding inside. But his slight build and fear of physical pain prevented him from acting on it.

Marcy Flores, the second baseman, was a Mexican who said his padre rode with Poncho Villa. His dark skin, straight, jet-black hair and wide nose made him a direct contrast to the rest of the team. Always smiling, his teeth shone like sparkling pearls. He spoke little English and understood less. He washed dishes at the King’s Crown and cleaned the office at the mine. He was only five foot three and weighed one hundred and twenty pounds but could cover the ground at second base better than any other player in the league. He was quick and the best bunter on the team.

My father heard that after two years with the Miners, Adolph Bronco talked Marcy into playing with the Vipers. But during his first season with the Vipers, Marcy had problems with Adolph for making a slur about his Mexican heritage. Marcy took off his shoe and raked Bronco’s face with his razor sharp spikes and then headed south. The best guess was for Mexico.

Except for his small, cone-shaped head, which made him continually adjust his mask, Myron Dey looked every bit the part of the catcher. His short legs put his thick body close to the ground. Curly brown hair sprouted everywhere — on his back, ears, nose, legs and arms — and a mono eyebrow lay in a thick line across the bridge of his nose. His deep-set eyes had a natural squint. The fingers on his throwing hand had all been broken or dislocated. They were gnarled and ugly. Though he was the smartest player on the team, you wouldn’t have thought so by looking at him.

Not a player over twenty-two years old and none weighing more than a hundred and eighty. They practiced after work and on Saturdays before they began their Saturday night drinking. Year in and year out, the team was just so-so. They won a few more than they lost but never against an island champion like the Victoria Vipers.

When my dad played his last season before moving to the states, they had a good year, losing only once to the Vipers by two runs.

The Vipers’ best player was their shortstop, a renegade Englishman named Nigel Cromwell who hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the ninth. As he pranced around the bases, he laughed, teased, and gave the raspberry to the downtrodden Nanaimo nine.

“He’s an arsehole,” said Jackson Whitehead.

“Yeah, a bloody prick,” remarked Jimmy Dolan, who by the way, served up the homerun pitch that lost that game.

Orphan Nigel Cromwell, moved with adoptive parents from England to the U.S. when he was two. Unfortunately, he turned out to be a pasty, pocked-faced, teeth-rotting thirty-two-year-old who had played some shortstop in the Brooklyn Dodgers farm system. He was arrogant, foul-mouthed, and ugly. But he was the Vipers’ best player, and he knew it. No one in the league liked him except his own teammates, and even that was questionable.

The league was set up so every team played each other twice, once at the opponent’s park and once at home. The Miners had lost in Victoria and were playing the final game of the season in Nanaimo.

The Vipers drove up Saturday afternoon, stayed at the Plaza, and drank at a small pub nearby. The Campbell House had only ten tables and no women’s entrance. The Vipers bragged, bullied, and chased everyone out of the pub. They stayed until the pub closed, at midnight. But just before midnight they bought several bottles of rye whiskey to take back to their rooms. When they returned to the Plaza, their hell raising continued and got so out of hand the night manager had to call the constable to quiet them down.

It was the home team’s responsibility to maintain and line the field. Nanaimo’s field was a working pasture behind the Lion’s Tooth Tavern, which was closed on Sundays because of the blue laws. On game day, the entire team would go out at daybreak and try to put the field in some sort of playing condition and then get to church.

Today, as was the seasonal custom, the Northeast winds blew rain clouds over Nanaimo. The showers soaked the players and left the field damp but not soggy. They knew the warm breezes of the Indian summer would dry the field in time for the game to be played.

The grazing cattle had to be put into a small holding pen behind centerfield until the game was over. They dragged the infield, smoothing out some of the ruts. The outfield was full of gopher holes and caused many sprained ankles and two broken legs that season. They’d bring shovels full of sand to fill all the holes they could see. If, during the game, a player spotted a dangerous rut, he’d kick dirt into it and try to level it out with their foot.

The grazing cattle maintained the grass, but the players had to watch where they stepped. The batters boxes and foul lines were marked using white flour, as lime was too expensive even if they could get some.

The dugout benches were so short the whole team couldn’t sit at one time. A roll of chicken wire was stretched between two wooden poles before each game to protect the players in the dugout from foul balls. Twenty feet back from each foul line were a pair of three-tiered wooden bleachers for the fans. Those who came early got seats. The rest just stood and drank flat beer they’d bought yesterday.

I knew you could bring it!!! The details of a game was life itself. Good job!