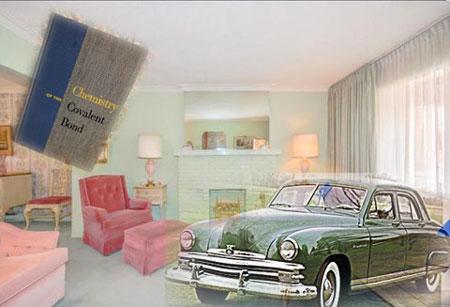

We settled down to study in the den, as she referred to it. Actually, it was an enclosed porch, well-windowed, with its own little heater attached to one of the walls, and well-furnished with a couch and two upholstered chairs. After a few study sessions, Mary became less of a distraction, and I began to enjoy the peaceful ambience of Mary’s home—ah, the quiet, the absence of harsh words.

“How’s your calculus coming?” Mary asked me, one evening.

“Fine—I understand it. Physical Chemistry is getting me down.”

“What’s wrong?”

“Professor Gage added quantum theory to the course. That’s his field.”

“It’s just differential equations.”

“I know—I need to brush up.”

“I’ve got a little book on it.”

She jumped up and went off somewhere in the house. She reappeared with the book, a well-known summary of that branch of mathematics.

“Can I keep this for a while?” I asked, after flipping the pages.

“Yes—I’ve already completed the course.”

On another evening, Mary’s family was having a late dinner, and her father invited me to their table. I declined the invitation, explaining that I already had dinner at home. There were other such invitations, and despite the good intentions behind them, I was beginning to feel uncomfortable. And worse, Mary’s mother noticed a patch in the knee of my trousers and offered me an unused pair of her husband’s trousers. Still worse, as Christmas approached, the family presented me with four pairs of socks, neatly boxed and wrapped in red-and-green paper. I hid my awkward feelings behind a smile and a thank you. I hadn’t even sent them a Christmas card. I was saddened when that horn sounded in front of my house the next time—and the next. I began mulling over ways to extricate myself from my present study arrangements without giving offense.

But one obstacle to my liberation was my own self-doubt. Would any sensible person in my position leave that kindly household? Would he consider himself, as I did, an object of charity? And there was that pleasing image of Mary—with her dark eyes and grand smile and that beautiful figure, displayed in those long, tight skirts of the 1950s. Ah, but what to do?

Well, my confused feelings made me a touch reckless. I decided to make an attempt at love. And so, one evening, as we pulled up at my house, I leaned over and kissed her cheek. It was just a simple affectionate kiss—but alas, she didn’t like it. In fact, she looked at me as though I had changed into Mr. Hyde.

“Don’t do that—not ever,” she said. “My boyfriend would have a fit if he knew you did that.”

“Oh—you have a boyfriend?”

“Yes, and he wants to marry me.”

“Really?—would you leave school?”

“Would I throw it all away? I don’t know—I don’t know.”

Well, well—she was in the midst of her own dilemma, one involving choices more difficult than mine.

“Why did you want me to study with you?” I asked.

“I knew you were a good student. I also learned you had a bad home life. One of your high-school friends sits next to me in English Lit. We got to talking about you.”

“So you wanted to help.”

“Well, yes—I wanted to help.”

“Were you also looking for somebody else?—for a friend? maybe a boyfriend?”

She thought for a moment and then whispered sadly, “Maybe—I don’t know.”

“Look, Mary—I’m grateful to you and your Mom and Dad for your kindness. You’re fortunate to have such a pleasant home. But I think it would be best if I studied at my house.”

“All right,” she said quietly.

“Just this once, let me help you—don’t go running off to Elkton to get married.”

“I won’t,” she said, again quietly.

Mary was silent and brooding when, for the last time, I climbed out of that Kaiser Manhattan. She sat for a while and then drove away. As I approached the front door to my house, I could hear Father and Mother in the midst of a squabble. They were troubled in their own way, but not in every way. And when I entered that imperfect place—well, I was home.