Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5

That moment, if I could freeze-dry it, pour boiling water on it once a month for the rest of my life, I told myself later, I’d be happy. Of course, I didn’t know that then, and, reporter that I was, had to press on. Question number two.

“What happened with your parents? And who takes care of Dandy?”

The warm space where her cheeks pressed my shoulder cooled. She propped herself up on one elbow.

“Mom died last June. Cancer.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Not as sorry as I am. She was my best friend. Always had the right answers for me, before I even asked. Had cancer for what seemed like forever, not even two years, really, and right up until the last month, I thought she’d make it. My sister, she knew better. But I couldn’t, didn’t, want to see that. I still talk to her, kind of, when I get confused. I asked her about you after the night in front of your folks’ house. She said, ‘Gretchen, why the hell not?’”

Tears moistened her extra texture.

“Anyway, Sheila, my sister, she takes Dandy most of the time.”

I didn’t want to press any more, but she seemed anxious to get the inquisition over with.

“Six months after mom, dad, he’s, or he was, 11 years older than mom. Heart attack.”

She vanished into an oversized Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young T-shirt and rolled over, back to me. “‘Nuff bedtime stories, man.”

I lay there in the dark, realizing that “man” was a perfect lover’s name when you have three—especially since I was neither Jack—but mostly thinking, Broad Street is OK.

Or not. In the morning bagel-and-coffee light, I smoked my usual before-work half-a-joint, and learned I should never to do that in her place.

“That stuff stinks,” she said as she dressed for work. “And you shouldn’t need it.”

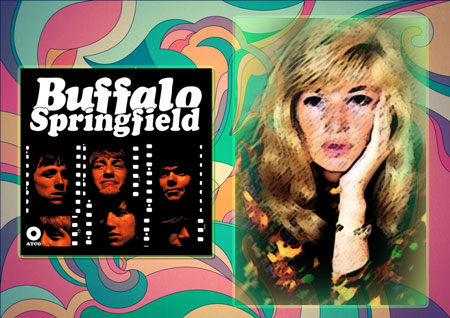

I pondered, then reconsidered, singing “Flying on the Ground is Wrong,” before heading out for the world of journalism.

And when I called later, after my regular shift, with a night meeting yet to come, hoping for a late visit, her voice was distant, almost like she couldn’t wait to get off the phone. Had I screwed up asking about her parents? Or was this a night to “hang out” with a Jack or two?

I thought back to the way we met, to the way she was, for good and bad, and let it go. Sort of. Take the fast with the too-fast, I figured.

Except the serial monogamist in me couldn’t let things well enough alone. I wasn’t really a free-love kind of guy. Can’t Gretchen be, like, an actual girlfriend? Or is she like Neil—don’t tie me down, got my own music to do?

Hoping for the former, I played on the latter, parlaying her dislike of the recorded version of one of Young’s ballads into a way to burrow deeper into her heart. Like many women I knew at the time, Gretchen had problems with “A Man Needs a Maid.” Except hers weren’t with the lyrics, commonly thought to be about a man yearning for a woman who’d, as the song went, “keep my house clean, fix my meals and go away.” (It was mostly about loneliness, as well as Young’s then-girlfriend, an actress famed for playing a maid-like movie character.)

Gretchen’s problem was with its instrumentation, heavy on orchestral strings. “Can hardly hear the melody for all that crap. I’d love to hear it without all that.”

So when a work buddy told me he owned a bootleg of a Young solo concert featuring the song, I borrowed it. He gave me a 90-minute window, just enough time to take it from his apartment to hers, play it, and return his treasured disc.

I called Gretchen from a pay phone, breathless with my find.

“Got something you’re gonna love, but just for a while. I’ll bring it over. You won’t be sorry.”

She didn’t seem all that interested. Didn’t even ask what it was. “OK. Hurry up. Got stuff going on.”

She let me in when I showed up, then disappeared into her bedroom. Through the shut door, I heard her in animated conversation, punctuated by giggled, “Yeah, yeah, sounds great,” and when she finally got off the phone after a “Yeah, OK, see you soon, Jack,” I had just enough time for my surprise.\