Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5

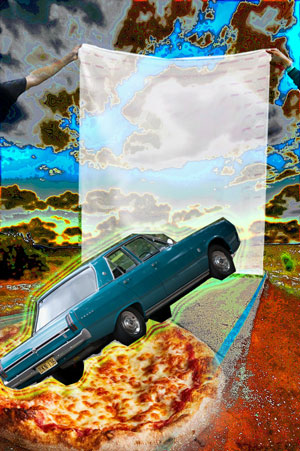

On a late-spring night half-a-century back, best as I recall, I drove a Plymouth through a restaurant napkin and entered another universe.

Of the first I’m reasonably sure; second, certain.

It was a time of infinite possibility, near-probability, life all full ahead, fears masked in male bravado, if there at all, and as the black rotary phone in my bedroom shot unanswered rings at Phil’s place, it was like I could hug the future. And expect it to hug me back.

1970, 18-edging-toward-19, was the last year I’d live with my folks in their West Oak Lane, Philadelphia home, which has housed most dreams since, regardless of my sleep-world’s time-period and denizens.

On the wall of that room—little larger than a closet—I’d scribbled a pathway to freedom by penciling a few memorable lines from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, celebrating the “mad ones” who want everything, simultaneously. A few feet from Jack’s quote rested, uneasily, that well-thumbed paperback and a few others in the first rung of a small metal book-case: Richard Farina’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me; J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye; William Goldman’s The Temple of Gold; Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus; Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha.

My collection of tomes weighed like stones in a David-model slingshot aimed at something—or, in my mind, someone—blocking me from independent adulthood.

As it was my nature to view most everything I did as part of an endless soul search, these were my “find-yourself-already” novels, destined to forge an interstate to urgent destinations—wisdom, career, loss of virginity. Not in that order.

My call to Phil’s pealed madly, and I lapsed into one of many imaginary arguments with this long-time friend—my designated Goliath—who I loved dearly for all the great moments we’d shared, the summer in Europe we were about to blaze, and resented, because most of those times were his, me tagging along, laughing at his jokes, playing his outrageous what-me-worry sidekick shadow.

Why can’t you ever listen, Phil? Must you always pole-vault over whatever I say and make it your story? If I manage a good grade, you get a better one, and if I gain ground with a girl, you make more with a prettier one…or so you claim. How come I can’t slash your Saran Wrap-like prison around me? Will eight weeks across the ocean yielding to your stifling, if fascinating, aura leave me unable to burst unshackled and genuine, into my 20s?

My door rocked open, pulverizing my navel-gazing, and Phil burst inside, Art Carney into Jackie Gleason’s apartment, all 5-feet, 8-inches (one up on me, of course), Wrangler jacket, jeans, sneakers, on which he whirled, then stretched his scrawny (less so than mine) arms (hairier), pressed his hands on my books, squeezed volumes together in accordion fashion and elevated them towards the ceiling like a cascading deck of cards until they fanned out and detonated. Farina careening into my (mono) record-player. Kerouac sliding along the third-baseline of my hard floor. Hesse crashing against the “mad ones” quote. Goldman, Salinger, slithering under the bed. Roth splat! against the window.

Phil forced his stubbly face almost into mine and invoked my childhood nickname, along with the mission squirming in my scattered paperbacks.

“Change your life, Stutz!”

I gathered the books—fat chance he’d pick them up—and restored them to their vaunted spots.

“Where the fuck you been? I call, no answer, then suddenly you emerge, some amok Wizard of Oz flying monkey. How?”

“My sister dropped me off, man.” He cast a judgmental eye at my Kerouac wall. “Can you get the Bozo-mobile? Chance-of-a-lifetime sizzling at Continental Pizza.”