Page 1 Page 2

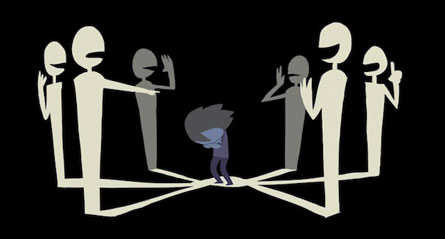

Still from “To This Day”

The form of the short film has always been a deep draw for critics and art lovers, especially the ones found in places like Wild Violet. Something about the medium gives it a depth that isn’t always created on full-length feature films, which devote themselves to following a predictable narrative building up to an action-packed ending in mainstream cinema. Oddly enough, the restrictions which short film-makers face — duration, budget, and resources — help create a finished piece which is obsessively conscientious about style, form, and substance. With anywhere from 8 minutes to half an hour to sweep up the audience (or isolate them) and convince them of something, it’s not a technique which is taken for granted.

Working Behind the Social Lens

What can be crafted into something poignant and revelatory only needs a matter of minutes to accelerate. Think of the massive following of Shane Koyczan’s beautifully scripted “To This Day”, a powerful animation/spoken word about bullying which took over social media like a frenzy a few months ago. Like its literary counterpart, the short story, a film can either build up from one solitary element or begin in medias res. A lifetime of conflict or one profound moment to set itself out into the world can be captured within a savvy lens, and often the moments are strikingly serious, with a branding of irony on the side. It raises the question of why short film leans towards the dark and mysterious — perhaps because, in the spectrum of human nature, the most passionately received stories are the ones that are stricken with tragedy — or maybe short film is the perfect format to draw attention to social issues. “To This Day” is a heroic reflection on the long-term effects of bullying and a recollection of their origins, serving as an active demonstration against the expectations and behaviors which beat down an individual’s uniqueness and the rising crescendo of voice, intensity, and succession of events enflame both a compassionate and vigilant uprising against these adversaries, making it a staunch addition to the anti-bullying campaign taking off across North America. It’s a kind of memoir/tribute/obituary/call to action which finds its voice effectively through vibrant, honest visuals and carefully crafted words, and sometimes that can be just enough to send out the air of change — not too long to watch, but long enough to resonate.

The Frontier of New Ideas

Short film isn’t subject to the same kind of restrictions like its larger-than-life relative which rakes in billions each year. It doesn’t have to sell tickets, seduce the big corporations, or mingle the masses. Instead, it has to sell ideas, grant applications, and entries into film festivals. So perhaps this is why short film is the avenue of pressing social change. Without discounting the Hollywood contenders which do venture into challenging territory (usually after the fact when it is “safe” to do so), and the excellent selection of independent film industries across the globe which have always pioneered their own way into the darker avenues of the public psyche, short film is more likely to reach out and experiment with new and innovative measures. Understandably, with mainstream film providing the entertainment aspect over the art aspect, people in general don’t want to sit back and pop their corn to something too heavy over the course of two hours. Short film doesn’t have to trouble itself with this — it can sway art and entertainment to its celluloid heart’s content.

In fact, short film often confronts the artistic value of its bigger counterpart as well as complimenting it, defying the foundation of the industry itself. Take a look at Kibwe Tavares’s magnificent “Jonah,” a visual masterpiece and sensuous cautionary tale against humankind’s addiction to excess and glamour — ironically triggered by a lens. The transformation of an untouched fishing community on the African coast into a glistening tourist mega spot and its descent into a cesspit of squandered wealth is unnervingly organic. The transitions are graphically seamless as vibrant motifs blossom out of the pristine shores, bringing life and salvation from boredom and progressing into an alarming acceleration of contemporary problems like overpopulation, pollution, crime, and ultimately a sense of disillusionment and a loss of self. It is a simple narrative conveying that universal warning about striving for too much when everything that is essential already lies at our feet, and the viewer is left with a sense of desolation from the film’s closure (or lack of) — demanding that the “right” conclusion must come from the audience itself by their actions outside of the screen. Despite being an age-old tale (aside from its biblical allusions) which has appeared in literature and film for countless ages — the plight of destroying the old with the new — it remains refreshing, particularly at the beginning where one viewer may interpret the transformation as good, a form of empowerment and enterprise for a developing nation. In a potentially reductive interpretation that may be perceived as under-mindedly Eurocentric, it is a defiant rejection of colonial imposition. (Under-mindedly Eurocentric because not every struggle or victory has to be associated with any kind of Western influence, even though the stifling juxtaposition of capitalism certainly takes its roots from there).

Page 1 Page 2

Pages: 1 2